Post-colonial Fabrics in Contemporary African Art

There are certain visual patterns that occur frequently in the imagery created by African and Afro-diasporic artists. One such image is what I am terming the post-colonial fabric template. What I mean by this is that varieties of cloth or patterns such as Ankara, kitenge, Dutch wax print or batik, are set up as a background to a Black subject who poses in front in either similar or contrasting color scheme. Dutch wax print for example, can be understood as a post-colonial African fabric. This is because its designs were originally based on Indonesian batik, and it was manufactured by the Netherlands and Britain and brought into markets in West African colonies. Dutch wax print was rejected as an aesthetic in Indonesia and in Europe but embraced by West Africans for symbolic, aesthetic and cultural use. Today it is deeply integrated in the wide range of sartorial expressions that define contemporary African cultural identity. The creative incorporation of fabrics which are linked to colonial trade into African material culture has allowed for the assertion of an Afro-modern cultural identity that stands in contrast to colonial notions of a primitive and unchanging ‘essential’ African. This essay reflects on the use of post-colonial fabrics as a critical intervention on identity politics, as a grammar that informs the reading of post-modern African artworks, and considers the limits of its usefulness in the deconstruction and re-imagination of what it means to be ‘African’ in the 21st century.

Colonialism left in its wake histories of trade, imperial war and domination, cultural syncretism and the invention of new ‘traditions’ linked to the institutionalization of colonial racial and gender politics. Progressive scholars and artists who reckon with this history draw our attention to Africa’s pre-colonial history of re-formulating identity and tradition, reminding us that changes in African cultural tradition are not necessarily new or exclusively colonial. Yet they also show us that such colonial creations were distinct in their essentialist ideas about race, blood and ethnic purity. Scholars like Mahmood Mamdani tell us that the invention of the ‘indigene’ was part of the colonial project of ‘fixing’ race and ethnicity as categories which determined the allocation of rights and power. Artists like Yinka Shonibare and Malick Sidibe tell us that despite the violent relationship between Africa and Europe, post-colonial constructions of individual identity were created through, and against the frame of Western modernity, eschewing cultural rigidity but nonetheless remaining within the Western imagination of ‘civilization.’ Malick Sidibe’s studio portraits reveal a great longing by Malians to possess goods linked to Western industrial modernization which signaled class and status, while Yinka Shonibare’s installations offer us humorous and mocking renditions of European high culture. Further illustrating the tensions between violence and culture, other post-colonial fabrics that have entered the ‘traditions’ of African attire despite the legacy of colonial genocidal assault include the Hererotracht worn by Herero women living in Namibia, Botswana and Angola, whose fabric patterns have been combined with the structure of 19th century Victorian dresses introduced by German missionaries. Thus, as Nancy Hughes explains in an essay co-authored with John Picton entitled “Yinka Shonibare,” the post-colonial fabric is “an industrial, mass produced, modern product,” yet it is also a signifier of an Afro-modern identity created through and against the frame of colonial ideas around race and ethnicity.

Dutch wax print. Images courtesy of Vlisco.

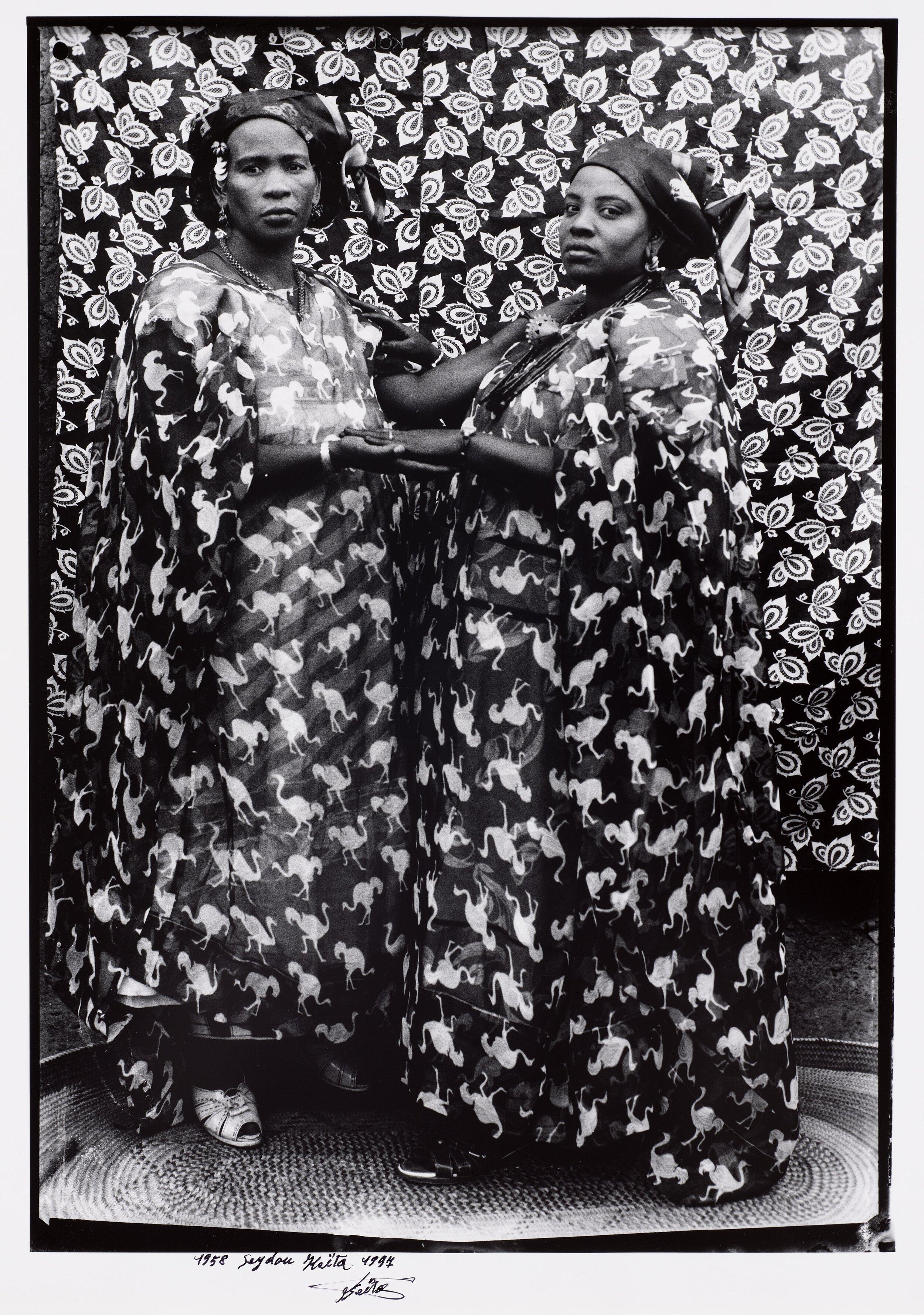

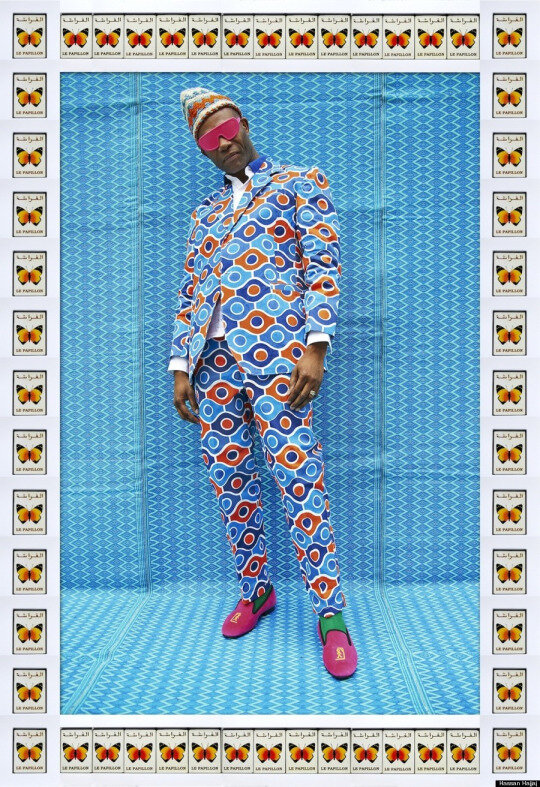

African and Afro-diasporic artists employ the post-colonial fabric as a template most often through the medium of photography. Salah Hassan has pointed out that photography has been a highly influential image-making medium of the 20th century. He explains in his article “<Insertions>: Self and the Other in Contemporary African Art” that idea-based art and conceptualism has dominated photography since the 1960s, resulting in the fact that most post-modern artists use it to “deconstruct cultural mythology, stereotypes [and] modernist ideas of creative originality and authenticity.” Examples of the post-colonial fabric template can be seen in the works by the following artists: Seydou Keita in Untitled/Two Women (1958), Omar Victor Diop in A Moroccan Man 1913 from the “Project Diaspora Self-Portrait Series” (2014), Kehinde Wiley in Samuel Eto’o (2010), Hassan Hajjaj in My Rock Stars Series (2012), Samuel Fosso in The Chief: The One Who Sold Africa To The Colonials (1997) and Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou in Untitled from the series “Dahomey to Benin” (2010). Although the works of these artists engage different historical time periods and narratives, the template nonetheless serves as a visual grammar to signal the presence of an Afro-modern identity as a background that informs the reading of the text.

Seydou Keita, “Untitled” (“Two Women”), 1958

A Morrocan Man 1913 by Omar Victor Diop from the series Project Diaspora Self-Portrait (2014)

Samuel Eto'o (2010) by Kehinde Wiley

Portrait by Hassan Hajjaj from the series My Rock Stars Series (2012)

The Chief: The One Who Sold Africa To The Colonials (1997) by Samuel Fosso

Leonce Raphael Agbodjelou in Untitled from the series “Dahomey to Benin” (2010)

20th century Malian photographer Seydou Keita is perhaps best known for capturing Mali’s engagement with Western modernization using the background of the post-colonial fabric. His contemporary, Malick Sidibe has also shown the ways in which popular culture in the 1960s in Bamako departed from notions of ‘traditional’ or from the binary of ‘true’ versus ‘false’ African attire to embrace globalized Western attire such as suit coats, bell-bottoms and frocks. Hassan Hajjaj in his My Rock Stars photography series acknowledges the legacy of photographers such as Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe in his own work which engages postcolonial identity in the juxtaposition of ‘traditional’ Muslim clothing such as the hijab, North African cultural practices such as Moroccan biker culture and Western commodity culture such as the Nike clothing brand. Similar work on North African identity using a post-colonial template has been done by Arwa Abouon who interrogates the intersection between Western, Amazigh and Muslim culture, and Lalla Essaydi who explores questions of gender and religion in Le Femmes du Maroc (2008)

Portrait by

Lalla Essaydi from her series Les Femmes du Maroc (2008)

The post-colonial fabric as a background articulates the kinds of identities that Africans have embraced and invented in the wake of colonialism and the impact of Western commodity culture. The works are usually simultaneously an acknowledgement, a critique, and an assertion of that identity. These artists’ works deconstruct essentialist notions about what constitutes the ‘authentic’ African in fabric, dress or identity and attempt to carefully and thoughtfully depict the way ‘African’ is constructed through aesthetics and through culture in ways which undermine the dualisms between the ‘traditional’ and the ‘modern.’ Their work points to the fact that post-colonial African identity has been constituted within the historical contexts of colonial trade, slavery, migration and globalization, but is not less ‘African’ today than anything invented in the pre-colonial era. Their works argue, as Stuart Hall did in his 1994 piece “Cultural Identity and Diaspora,” that identity is always a “production which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.”

How To Blow Up Two Heads At Once (Ladies), 2006 by

Yinka Shonibare

Post-colonial identity through fabric has also been brilliantly explored by artists like Yinka Shonibare, El Anatsui and to a lesser extent, also Nick Cave. As Nancy Hynes and John Picton reveal in their essays “Re-dressing History” and “Undressing Ethnicity,” how Shonibare himself is an example of the complexities of post-colonial African identity, as he accepts the labels “Yoruba” “Nigerian” “Black British” and “African” as long as they are not used as a means of “fixing him.” Their article which appeared in the African Arts journal in 2001 also shows that Shonibare combines postcolonial African fabrics with Victorian signifiers to comment with wit and humor on “the entangled relationship between Africa and Europe and how the two continents have invented each other.” Shonibare’s work critiques modernist notions of ethnicity, race and ‘authenticity’ in the stereotypes of black and African people in the Western world. In an interview conducted with Nancy Hynes in 1996, Shonibare warned against locating African ‘authenticity’ in materiality and objects such as cloth:

“Sometimes people confuse representation for what it represents. But they are not that physical thing - they don’t exist in the world that way. So if you see a woman walking down a road and she’s wearing African cloth, you might think – now there’s African-ness, true Africanity. But the cloth, those clothes, are not African-ness.”

Similar to Salah Hassan’s discussion of the feminist critique of modernist representation in his essay “<Insertion>: Self and Other in Contemporary African Art,” Hynes and Picton point out that Shonibare follows the school of deconstruction that artists like Helen Chadwick have done for the signifiers of femininity. The idea of ‘authenticity’ and ‘African-ness’ compares with the idea of ‘women’ and ‘images of women’, in that essential identity does not exist in any ontological sense save for in the imagination of what Laury Mulvey has termed the (historically white) male gaze.

Pre-colonial and post-colonial African fabrics exist side by side in constant conversation with African identity. Both of them are valid expressions of being African, because African-ness is not inherent to the fabric, but is constructed when cultural significance is ascribed to forms of representation at different points in history. African-ness is the result of people collectively deciding at a point in time through deliberation, contestation or popularization what to take or leave in a process of cultural exchange and creation. African identity is not determined through the binary of ‘true’ versus ‘false.’ In his insightful essay, “The Trade in West African Art” which appeared in the African Arts journal in 1991, Christopher B. Steiner points out that the creation of African art objects involved the use of ritual across ethnic boundaries, as well as the world economic system. It also intersected with the articulation of Islam and other world religions and the influx of Western manufactured products. Steiner’s discussion of trade in art objects in the Cote D’Ivoire art market shows how globalizing forces, local artistic expression, Western manufactured goods and tourism drove the creation of invented genres and styles, constituting new forms of African cultural expression which were tied to both commodity and symbolic value.

This means that the history of post-colonial aesthetics in Africa cannot simply be equated to what is commonly understood today as cultural appropriation in the pejorative sense – that is, the short-lived, careless, and ostentatious use of African cultural symbols for profit and for power while simultaneously erasing its cultural origins, resulting in what bell hooks has termed the act of “eating the Other.” Postcolonial fabrics are embedded in the lived, meaningful practices of expressing cultural identity and belonging in Africa. As John Picton explains, Dutch Wax print acquired a specific meaning for West Africans like Ghanaians:

“African-print fabrics emerged in the nineteenth-century Dutch attempt to undercut Indonesian batik production through [mechanization]…the Indonesians rejected these fabrics [but they] found favor on the colonial Gold Coast…though produced in Europe, it manifested an aesthetic which was clearly of no appeal there…[Gold Coast] sensibilities began [in] the visualization of the proverbs [of] Twi-speaking peoples. The earliest dated cloth is the still-popular “Hands and Fingers” pattern, which was in production by 1895. In Ghana it is called “The Palm of the Hand Is Sweeter Than the Back of the Hand,” for the palm is where we hold on to good fortune…“Staff of Kingship” is another still-popular pattern, its design [is] based upon a wrought-iron sword captured from the Asante.”

Dutch wax print

In a similar vein, Ghanaian artist El Anatsui’s makes large sculptures with bottle caps which often read like woven pieces of kente cloth to offer another kind of commentary on Afro-modern culture and the tri-continental colonial/post-colonial exchange. In his interview with art critic Okwui Enwezor from the piece “Cartographies of Uneven Exchange: The Fluidity of Sculptural Form, El Anatsui in Conversation with Okwui Enwezor,” (2011) he reminds his audience that:

“I’m also talking about a larger history, the history of the African continent. You know, how did drink come to Africa? These alcoholic drinks came to Africa, brought by European explorers or traders long ago, ostensibly to serve as items for barter or trade, which was what they were used for initially. But then, as time went on, we saw that the drinks happened to be one of the items that made the rounds in the transatlantic trade...So working with bottle caps makes me feel like I’m using a medium which was there at a particular time in history, when the contact between the three continents started.”

Between Heaven and Earth (2006) by El Anatsui

Finally, Nick Cave’s “Soundsuits” sculptures offer a unique kind of commentary by narrating a reversal of the history Afro-modern identity construction. He begins with seemingly futuristic, highly fantastical and humorous other-worldly ‘suits’ made of beads, sequins, plastic and metal, but then often molds them into shapes that resemble the clothing and fabric used in ritual West African masquerades. He thus presents an Afro-futuristic narrative through imagination, myth and ritual as the starting point for the creation of Afro-diasporic identity.

Nick Cave, Soundsuits (2004)

21st century artists, particularly those working in popular cultural forms such as fashion, music and graphic design, continue to reproduce the post-colonial fabric template through fashion editorials, album art, film and commercial photography. This can be seen for example in the work of young artists like Brad Ogbonna’s,“we were once kings” (2014), Flo Ngala’s Untitled (2015), Mukhtara’s “Bantu Migrations: discourses on wearing home” (2015), and in the Abderrahme Sissako’s film, Waiting for Happiness (2002). However, this use seems to flow from the fact that the template now has currency in the global art world and in popular media. In many ways, this usage avoids seriously reflecting about what it means to be ‘black’ or ‘African’ in the 21st century. The post-colonial fabric template can become a conservative way of imaging where for example, an artist working in fashion may simply borrow it as a popular signifier. ‘African print’ becomes a one-liner, where a Western shirt, trouser, dress or suit coat becomes more ‘meaningful’ when afro-centric patterns or accessories are added. Non-western shapes such as the dagaakporo (Dagaare), slit-and-kabba (Akan), dirac (Somali), Tagelmust (Tuareg) or djellaba (Berber) are usually relegated to ‘traditional costume.’ On the other hand, a different kind of conservatism is one that calls for the re-essentialization of African fabrics. This includes claims to ‘indigenous’ or ‘local fabrics’ as ‘true’ African fabrics over those tied to colonial trade – the assumption being that they originated in a ‘pure’ and autochthonous way, in a culturally isolated pre-colonial African space. This imagination does not hold up to historical analysis as Christopher Steiner points out, because “at no time has African art existed in total cultural isolation.” In their valuable book, A History of Art in Africa (2008) Monica Visona, Robin Poynor and Herbert M. Cole show that African artists have “long looked outside their own communities for sources of inspiration” in order to fuel artistic innovation particularly during dynastic eras in kingdoms like Benin (13th C. – 19th C.), where kings coming to power required new forms of art or textile designs to distinguish their reigns. Regions in East Africa such as the coastal city of Kilwa in Tanzania or Madagascar show how art traditions have been influenced by ancient maritime trade with Arabia, India, Indonesia and the South pacific.

Still from Waiting For Happiness / Heremakono (2002) by Abderrahmane Sissako

Flo Ngala, Untitled (2015)

Brad Ogbonna, We Were Once Kings (2014)

In fashion, the attempt to re-essentialize African fabric by claiming autochthony is undermined by the fact that most claims to ‘true’ fabric are not advertised toward masses of Africans, and are not in conversation with the things that are social and culturally relevant to them, neither are they being created using the geometric shapes of older African styles – rather, most newly-designed ‘authentic’ African clothing falls squarely within ‘Western’ modes of dress. The challenge for creators working today is to decolonize and create new frames for representing post-modern African cultural identity without making essentialist claims which seek to negate everything created in the post-colonial era - dismissing it as a simple result of the colonization of the mind. The notion of cultural purity (that is, of African creations ‘untainted’ by Europe or another Other) is in fact itself a racialized and colonial notion. It is not based on the historical experience of practiced belonging or identity on the African continent. Africa has always been a place of movement, trade, syncretism and invention. No innovation has ever been culturally singular.

Moreover, the art that uses the post-colonial template to recreate past narratives does not seem to be critically investigating our contemporary world. More often than not, it seems to be predominantly engaged in reclaiming an African ‘coolness’ and also in finding an African/Afro-diasporic iconography that disturbs the white narratives. Think for example, of the ‘inverted’ images where black subjects replace canonical European figures such as Kehinde Wiley’s Down (2008), Kudzanai Chiurai’s Moyo (2013) and Andre Serrano’s The Interpretation of Dreams (The Other Christ) (2001). This is also a motif that has been heavily reproduced by artists across race and nationality for example in Marina Abramovic’s Anima Mundi (Pietà) (1983), Rotimi Faniy Kayode’s Every Moment Counts (1989) and Renee Cox’s Yo Mama’s Pieta (1996). Fine artists and creators of images of post-modern African identity should reconsider the usefulness of the post-colonial template. While the ‘inversion’ of a white representation may seem radical, this expressive modality is still tied to the white gaze. I’m looking forward to more art that breaks the containment and repetition in the post-colonial fabric template and begins within new frames.

Still from Moyo (2013) by artist Kudzanai Chiurai. As part of the exhibition Harvest of Thorns, 2013. Courtesy of Goodman Gallery

Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies)(1989) by

Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Yo Mama's Pieta (1996) by Renee Cox

May 2020. Vol nº1